Preserving Maternity Services in Rural New York

- Sally Dreslin

- Feb 4

- 44 min read

Updated: Feb 10

Issue Brief by Sally Dreslin

PDF available here:

Key Takeaways

Rates of maternal death continue to rise, as do rates of severe maternal morbidity, which is much more common. Over the past 15 years in New York, the rate of severe maternal morbidity (considered to be a “near miss” of a maternal death) has increased by almost 70 percent.

Labor and delivery unit closures are occurring in safety net hospitals in urban areas, but the issue is even more pronounced in rural parts of New York.

As access to maternity care in rural New York becomes more tenuous with ongoing closures, and the hospitals that do provide maternity services experience increased operational pressures, the lack of proximity to basic perinatal care, much less the care required to manage higher-risk pregnancies, can lead to long patient travel times and increases in rates of maternal morbidity and mortality.

One of the most pressing needs in the effort to address climbing rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in rural New York is geographical access to services. Within the context of hospital and OB unit closures, the distance between maternity service sites is growing, and with increasing distance, risk also rises.

There has been a tremendous amount of work done in New York to address the high rates of severe maternal morbidity and maternal deaths, but it is difficult to receive evidence-based, person-centered, coordinated perinatal care when there is limited access to the providers and facilities where it is available.

In 2023, 40 percent of New York’s rural counties and 14 percent of its urban counties had no hospital-based obstetric services.

In 2024, responding to the need to ensure high-quality care in critical access hospitals (CAHs) and to address “our nation’s maternity care crisis,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services announced new conditions of participation to address emergency services readiness, transfer protocols, and obstetrics services, staff training, and quality. These apply to all hospitals and CAHs that have obstetrical units or emergency services (regardless of whether they provide obstetrical services).

In 2025 California enacted SB 669 to establish a ten-year pilot of a new care model— “standby perinatal services”—designed to preserve emergency-ready obstetric and newborn care at rural CAHs that can no longer sustain full, around-the-clock maternity units. It is designed to mitigate the risk that accompanies prolonged travel time to perinatal services. The pilot is not a replacement for comprehensive, person-centered care, but it may present an important opportunity to avert some of the worst potential outcomes in urgent scenarios when there is no other access to care.

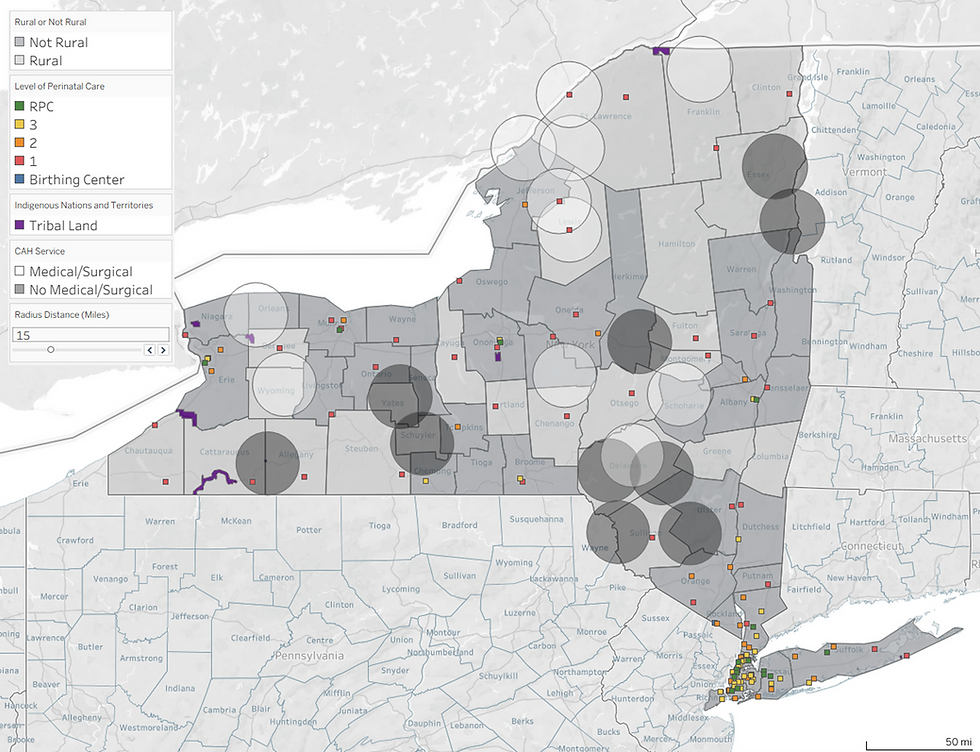

Maps developed in Tableau for this Brief show the distribution of maternity and birthing services in New York by perinatal levels of care, across rural and not rural counties, and relative to critical access hospital sites, highlighting distance-related access gaps relevant to a potential standby perinatal services pilot.

Introduction

This Issue Brief provides background information on maternity services in rural areas of New York and examines rural-tailored strategies, including care delivery and payment models that have evolved in the state. This paper also examines a new delivery model set to be piloted in California that may serve as a roadmap for preserving maternity services and improving access to perinatal[i] care in rural New York.

New York hospitals are increasingly struggling to achieve and maintain financial sustainability. Maternity services are often among the first to cease as hospitals and healthcare systems make resource decisions to improve their financial condition. Maternity services, among other services, are a savings target due to reimbursement that doesn’t cover stand-by costs or the cost of care, scarcity of specialized healthcare staff, and high costs of liability insurance, among other reasons.

Labor and delivery unit closures are occurring in safety net hospitals in urban areas, but the issue is even more pronounced in rural parts of New York. Distinct factors are driving rural closures, such as low population density and declining birth volumes.[ii] One percent of babies are born to mothers who live in rural counties, while 0.6 percent of maternity care providers practice in rural counties.[iii] When clinical services close in rural areas, patients often forgo care because there are no alternative providers, as there may be in urban areas.

In 2023, the March of Dimes published a report detailing state level data describing access to maternity care. The report examined data related to, “levels of maternity care access and maternity care deserts by county; distance to birthing hospitals; availability of family planning services; community level factors associated with prenatal care usage as well as the burden and consequences of chronic health conditions across the state.” Per the March of Dimes, New York is above the national average in terms of access to maternity care services with only 3.2 percent of New York State counties defined as “maternity care deserts,” compared to 32.6 percent nationally.

The maternity care access designations are as follows:

Despite the relative absence of “maternity care deserts,” New York does have a significant number of low-access areas. Most counties in the state are designated as federal Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSA) and within those, many are specifically designated as Maternity Care Target Areas (MCTAs) (see Appendix A for MCTA Scoring). MCTAs are designated on the basis of many components, such as the availability of maternity care health professionals, poverty rates, travel distances, fertility rates, social vulnerability, pre-pregnancy health status, prenatal care, and behavioral health factors.

As access to maternity care in rural New York becomes more tenuous with ongoing closures, and the hospitals that do provide maternity services experience increased operational pressures, the lack of proximity to basic perinatal care, much less the care required to manage higher-risk pregnancies, can lead to long patient travel times and increases in rates of maternal morbidity and mortality. New York has a regional perinatal infrastructure that is designed to support various levels of hospital capabilities and expertise, but managing the unpredictable nature of pregnant patients’ experiences can be challenging in a care system that is under considerable stress.

There is a robust body of scholarly literature that describes models of care that may be effective in addressing the various factors impacting maternal morbidity and mortality, examines the outcomes of the interventions, and examines associated payment reforms. New York has adopted a variety of programs and policies that are aimed at reducing maternal morbidity and mortality in all regions of the state. Recent reports[iv] released by the Maternal Mortality Review Boards of both New York State and New York City include descriptions of the factors that contribute to maternal mortality and maternal morbidity and propose recommendations to address these factors. The Boards categorize contributing factors using five “levels”: patient/family, community, provider, facility, and system.[v]

As the Step Two Policy Project discussed in our Policy Brief titled, Healthcare in Rural New York: Current Challenges and Solutions for Improving Outcomes, K.B. Kozhimannil and colleagues explored the association between a hospital’s obstetric volume and severe maternal morbidity[vi] in U.S. rural and urban hospitals. They found increased risk of severe maternal morbidity for both “low-risk and higher-risk obstetric patients who gave birth in lower-volume rural hospitals, compared with similar patients who gave birth at rural hospitals with more than 460 annual births. No significant volume-outcome association was detected among urban hospitals.”[vii] The authors do not recommend the closure of low-volume, rural obstetrics units, however, because of the higher risk “associated with increases in emergency birth and preterm birth, and travel distances are associated with adverse infant and maternal outcomes.” Instead, they recommend “rural-tailored” quality improvement activities, increased investment in rural clinician training, and creation of referral and transfer networks.

Background

Pregnancy-Related Mortality

Data on maternal morbidity and mortality in New York State present deeply concerning trends. NYS Department of Health (NYS DOH) data show an overall pregnancy-related mortality ratio[viii] of 18.5 deaths per 100,000 live births for the years 2018-2020 with Black, non-Hispanic women having a pregnancy-related mortality ratio five times higher than White, non-Hispanic women (54.7 versus 11.2 deaths per 100,000 live births).[ix],[x] In 2021, NYS had an even higher pregnancy-related mortality ratio of 23.3 deaths per 100,000 live births, with Black, non-Hispanic women having a pregnancy-related mortality ratio 5.1 times that of White, non-Hispanic women (54.0 v. 10.6 deaths per 100,000 live births).[xi] The NYS Maternal Mortality Review Board committees determined that 65.3 percent (32 women) of the pregnancy-related deaths in 2021 were potentially preventable. These trends are especially acute in rural areas.

Rural Pregnancy-Related Mortality

Nationally, the rates of pregnancy-related deaths are higher in rural (noncore and micropolitan) regions than in urban areas (large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro). These higher rates are generally attributed to a variety of sociodemographic factors, such as limited access to preconception healthcare that impacts preconception health status[xii] (i.e., chronic conditions including mental health issues), reduced access to reproductive and perinatal care services, and challenges with transportation, housing, and food.[xiii]

Rural Maternal Mortality

The only publicly available data on New York’s county-specific maternal deaths is the DOH maternal mortality data from the NYS Vital Statistics Event Registry as of 2023, which is presented on the NYS Maternal and Child Health (MCH) County Dashboard and consists of maternal deaths from any cause during pregnancy and within 42 days of the end of the pregnancy.[xiv] These deaths are further investigated to determine the extent to which the death was related to the pregnancy (see Key Definitions in Appendix B). The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) pregnancy-related data in the graph above includes maternal deaths during and within one year of the end of the pregnancy that are directly from a pregnancy complication, a series of events initiated by the pregnancy, or the worsening of a non-pregnancy condition by the physiological effects of pregnancy. The NYS maternal mortality data on the MCH County Dashboard is not directly comparable to the CDC data because it captures maternal deaths that have not yet been determined to be clearly related to the pregnancy (i.e., they are instead considered “pregnancy-associated” and are within 42 days instead of one year of the end of the pregnancy.

New York data shows high mortality ratios for rural counties in which a maternal death occurred during 2020-2022. New York’s most rural counties (those with the “noncore” designation) average the highest maternal mortality ratios across all urban-rural classifications (NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties), and the other rural counties (micropolitan) fall between New York’s small and medium metro areas, when averaged.

Chart developed using data from https://apps.health.ny.gov/public/tabvis/PHIG_Public/chirs/reports/#county

When comparing data geographically, it is important to remember that the highest-risk patients are generally delivering at regional perinatal centers that are located in larger metropolitan areas. Increased risk is not typically adjusted for in data related to maternal deaths.

Severe Maternal Morbidity

Additionally, rates of severe maternal morbidity — life-threatening complications during childbirth — continue to rise and inequities persist. As explained by the NYS DOH, “[S]evere maternal morbidity has increased significantly in New York State over the last 15 years. Between 2008 and 2022, statewide rates of severe maternal morbidity increased nearly 70%.” Across all pregnant populations in 2008, approximately one in 136 women experienced severe maternal morbidity, and by 2022, approximately one in 80 women did. The rates were inequitably distributed across racial and ethnic groups, although all populations showed a significant increase.[xv]

Severe maternal morbidity includes a range of unexpected, life-threatening complications of labor and delivery that can lead to serious short- or long-term impacts on the health and wellbeing of the mother, such as complications and procedures, including acute renal failure, acute respiratory distress, embolism, cardiac arrest, bleeding, eclampsia, sepsis, sickle cell crisis, mechanical ventilation, and hysterectomy. Severe maternal morbidity is a risk factor for maternal mortality. Importantly, though, the CDC indicators[xvi] of severe maternal morbidity are relatively narrow and do not include outcomes such as post-partum depression, chronic pain conditions triggered by pregnancy, or gestational hypertension,[xvii] for example, all of which can pose significant health risks and, in the case of postpartum depression, may result in pregnancy-related maternal death. As discussed below, mental health conditions were the leading cause of pregnancy-associated deaths between 2018 and 2021 in New York.

Because severe maternal morbidity occurs more frequently than maternal mortality—approximately 40 times more often[xviii]— and given its significant consequences, tracking and understanding it alongside maternal mortality is critical. A parallel approach offers a more complete understanding of risk factors involved in maternal deaths, many of which are potentially preventable. Data related to maternal morbidity support efforts to strengthen prevention, allocate resources, improve the quality of care, and address inequities to improve outcomes.

We see from the following table that rates of severe maternal morbidity have been rising overall since 2008, with significant increases in 2019/2020.

County-by-county data related to severe maternal morbidity provides additional detail on regions of the state that may benefit from enhanced prevention activities and interventions. In the graphic below, the counties in the darker shades of purple have higher rates of severe maternal morbidity, and the counties that are grey had so few cases of severe maternal morbidity, as currently defined, to report that the rates are suppressed.

Maternal Health Policy in New York

Care and Payment Models

Medicaid plays a significant role in the perinatal health landscape in the U.S., covering more than 16 million women and individuals of reproductive age and financing approximately 41 percent of all U.S. births. In NY, according to an analysis by KFF, in 2023, 49 percent of all births were covered by Medicaid with 49 percent of those in metropolitan areas and 43 percent in rural.[xix] In the current context of rising maternal mortality and a fragmented care system, states including New York are taking action with a variety of policy and delivery system innovations. These include expanding postpartum coverage, integrating midwives and doulas into service delivery, strengthening freestanding birth centers, and advancing coordinated models of perinatal care.

States have increasingly turned to care and payment model reforms that are designed to support accessible, equitable, integrated, and person-centered perinatal care. Nationally, the median income eligibility level as of January 2025 for pregnant individuals in Medicaid expansion states is 213 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), and in non-expansion states, 203 percent of FPL.[xx] In New York, as of February 2025, the income eligibility level for pregnant adults was 223 percent of FPL.[xxi] The federal option to extend Medicaid postpartum coverage from 60 days to 12 months is a foundational strategy, ensuring sustained access to care during a period when preventable maternal deaths are most likely to occur. Additionally, actions such as Medicaid coverage for doula services, maternal depression screening and treatment, and evidence-based perinatal care models like group prenatal care and maternity medical homes seek to improve outcomes.

At the same time, states are implementing payment model innovations to improve quality and reduce avoidable interventions. These policy shifts are supported by an infrastructure of perinatal advisory councils, quality collaboratives, and maternal mortality review boards. Together, these coordinated care and payment models reflect a recognition that comprehensive, accessible, and culturally responsive approaches are critical to reducing maternal morbidity and mortality.

New York has taken many of the actions described above. As described on the NYS DOH Maternal Mortality webpage and in the NYS OMH Maternal Mental Health Recommendations Report, the State has:

Extended Medicaid coverage through the postpartum period to 12 months following the end of pregnancy

Implemented Medicaid coverage for postpartum maternal depression screenings within the first 12 months postpartum

Provided incentive payments to hospitals and community-based providers

Increased Medicaid reimbursement rates for midwifery services

Expanded Medicaid coverage for the maternal population to include nutrition counseling, community health worker, and enhanced remote monitoring services

Maintained a directory of doulas who provide covered services to Medicaid members and, as of March 1, 2024, covered doula services for pregnant, birthing, and postpartum Medicaid members

Issued a statewide standing order that affirms all New Yorkers who are pregnant, birthing, or postpartum would benefit from doula services and allows doulas to provide physical, emotional, educational, and non-medical support before, during, and after childbirth or at the end of pregnancy through 12 months postpartum

New York’s updated Medicaid Perinatal Care Standards will be effective February 1, 2026. These standards apply to all Medicaid perinatal care providers, regardless of type, whether fee-for-service or Medicaid Managed Care, and regardless of clinical setting. The updated policy addresses issues related to: provider practice guiding principles, the principal maternal care provider, access to care, presumptive eligibility/Medicaid coverage, comprehensive prenatal care risk assessment and approach, care planning, coordination of care, home visits, initial and comprehensive postpartum visits by the principal maternal care provider, and feeding.

In addition to NYS Medicaid, the Essential Plan (New York’s version of the ACA’s Basic Health Program (BHP)) and the New York State of Health (NYSOH) Marketplace have been important health policy levers in supporting access to equitable, integrated, and person-centered perinatal care. In their paper New York’s Basic Health Program Increased Subsidized Insurance Coverage from Preconception to the Postpartum Period, Eddelbuettel and colleagues determined that, for eligible individuals (income levels between 138 and 200 percent of FPL and not eligible for Medicaid),

“The implementation of New York’s BHP was associated with an increase in preconception coverage from NYSOH, as well as an increase in continuous publicly subsidized coverage before, during, and after pregnancy, which is a time when churning in health insurance coverage is common and can be especially harmful for maternal and infant health.

“Although the BHP was not associated with a statistically significant reduction in preconception uninsurance, increased coverage from the BHP likely facilitated cost savings for individuals and improved continuity of care. We observed a substantial magnitude of substitution to NYSOH coverage away from private coverage in New York after BHP implementation.”

Further policy activities established in New York include:

The New York State Perinatal Quality Collaborative (2010)

Regional Perinatal Centers

The Maternal Mortality Review Board (2019)

The Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Advisory Council (2019)

The Hear Her Campaign

Family planning and teen education

The Perinatal Infant and Community Health Collaborative

The Nurse-Family Partnership and Healthy Families New York programs

The New York State Family Planning Program

In 2023, HRSA awarded NYS DOH a five-year Statewide Maternal Health Innovation Grant with the purpose of reducing maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity. The grant has three high-level goals. Goal One involves establishing a Maternal Health Task Force that performs a needs assessment, develops a strategic plan, engages partners, and annually re-evaluates and updates the strategic plan to align with overall efforts to reduce maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity and promote innovation and collaboration across the state. Goal Two involves the improvement of state-level maternal health data.

Goal Three of the Maternal Health Innovation Grant focuses on improving access to evidence-based care in geographic areas that have limited or no care. This goal would be considered a “rural-tailored” strategy. Goal Three is split into two projects. The first project is to establish virtual postpartum visits through partnerships with local hospitals that have maternity services and home visiting programs (to facilitate comprehensive support), in two rural counties – St. Lawrence and Chenango. The second project is to establish a perinatal Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (ECHO) project to enhance peer learning among “geographically diverse” maternal health clinicians. The hubs of the ECHO perinatal ECHO project are the University of Rochester Medical Center and Westchester Medical Center, both of which are NYS-designated Regional Perinatal Centers providing what is sometimes referred to as “level four” perinatal care.[xxii]

New York has also taken significant steps to address maternal mental health. Mental health conditions, including substance use disorders, were the leading cause of pregnancy-associated deaths between 2018 and 2021.[xxiii] The NYS Office of Mental Health convened a Maternal Mental Health Workgroup and issued a Recommendations Report in November 2025. The Report identifies “Rural Birthing Persons” as an “underrepresented population vulnerable to maternal mental health and/or substance use challenges.”

In order to better address maternal mental health and substance use challenges in NY, the Workgroup recommended efforts to enhance the following areas:

• Project TEACH • Maternal mental health & substance use programming/infrastructure • Collaborative Care Medicaid program • Dyadic care • Workforce development • Public awareness & education • community engagement • Child welfare • Screening • Peer support • Doulas • Treatment & care coordination • Data & quality improvement • Coverage & benefits.

Hospital Care and Maternity Services

Despite the many policy and payment efforts in New York, high rates of severe maternal morbidity and mortality persist. Maternal health outcomes are impacted by many factors, including racism and bias; social determinants of health such as housing, nutrition, transportation, and income; geography; health status; healthcare provider shortages; healthcare infrastructure, including access to services; health behaviors; insurance coverage; and more. There has been a tremendous amount of work done in New York to address the high rates of severe maternal morbidity and maternal deaths, but it is extraordinarily difficult to receive evidence-based, person-centered, coordinated perinatal care when there is limited access to healthcare providers and facilities.

Access to Healthcare Services

Across the U.S., more than one hundred rural hospitals have closed during the past decade, and more than seven hundred are currently at risk of closure due to financial pressures.[xxiv] The drivers of this financial unsustainability include losses from the provision of patient services, inadequate resources from other sources to offset patient care losses, and low baseline financial resources.[xxv] These result from many basic rural characteristics such as workforce shortages, low patient volume and low population density, long travel distances, limited local tax revenues, old and inefficient infrastructure, inadequate internet access, and “populations that are sicker and poorer and … have worse health outcomes than … their non-rural peers.”[xxvi]

Access to Maternity Services

With this national context of closing and at-risk rural hospitals, New York is not facing the challenge of ensuring accessible, equitable, sustainable perinatal services alone. According to a study done by K. Kozhimannil and colleagues, between ”2010–22, seven states had at least 25 percent of hospitals close their obstetric service lines. By 2022, more than two-thirds of rural hospitals in eight states were without obstetric services.” Their graphics demonstrate differences in hospital-based obstetric services by state in rural and urban areas:

In 2024, responding to the need to ensure high-quality care in critical access hospitals (CAHs) and to address “our nation’s maternity care crisis,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced new health and safety requirements for the provision of obstetrical services that, “set baseline standards for the organization, staffing, and delivery of care within obstetrical units, update the quality assessment and performance improvement (QAPI) program, and require staff training on evidence-based maternal health practices.” These new conditions of participation (CoPs) address emergency services readiness (including but not limited to obstetric (OB) emergencies, complications, immediate post-delivery care),[xxvii] transfer protocols more generally, and obstetrics services, obstetrics staff training, and the QAPI program. They apply to all hospitals and CAHs that have obstetrical units or that have emergency services (regardless of whether they provide obstetrical services). They do not apply to Rural Emergency Hospitals (REHs).

Full compliance with the updated and new CoPs is required by 2027, and the effective date phase-ins are the following:[xxviii]

The focus on enhancing the training and expertise of emergency department (ED) staff in OB emergencies, included among the requirements in the Emergency Services Readiness CoPs, is important and timely as dedicated maternity services evaporate and EDs become increasingly likely to receive OB and postpartum patients who are in crisis in rural areas. New York’s Regional Perinatal Centers can play an important role in this readiness training.

Lamb and colleagues in their February 2023 Policy Brief, Obstetric Readiness in Rural Communities Lacking Hospital Labor and Delivery Units, prior to the release of the updated CoPs, called for the federal government to require and fund “ongoing training for the existing workforce.” Including:

“a. Annual obstetric recertification training for all rural providers working in emergency departments, including Basic Life Support in Obstetrics (BLSO), Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO), and Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP). This training should be required in areas where there are no labor and delivery units within 30 miles, as these providers are the nearest form of obstetric emergency access. When possible, offer this training free of charge and remotely to reduce barriers (remote training is particularly critical to minimize travel time, given the extreme shortage in workforce).

“b. Regular simulation training for various obstetric procedures and emergencies. This training should be offered free of charge and available remotely to reduce barriers.

“c. Ultrasound training for rural providers working in emergency departments. Encourage hospitals, as funding and collaborating network provisions allow, to stock maternal monitoring equipment and technology for antepartum surveillance.”

Their Brief also encourages the establishment of relationships between rural ED clinicians and regional specialists for “1) telemedicine consultations in real time and 2) opportunities for rural ED providers to rotate at higher-volume facilities for exposure to diverse obstetric cases and different levels of care.”

Many of the recommendations align with those proposed in the 2022 CMS report, Advancing Rural Maternal Health Equity. There are recommendations related to enhancing the doula workforce; encouraging CMS to require the creation of quick-access hospital toolkits for common OB emergencies; providing rural EMS agencies with telemedicine and equipment to better manage OB transports; creating regional, interdisciplinary OB quality improvement teams; adopting regional telehealth programs; and modifying financing related to Medicaid reimbursement and funding through the HRSA Rural Maternity and Obstetrics Management Strategies grant program (NY has not been in any of the award cohorts).

Rural New York

As previously discussed in the Step Two Policy Project’s Policy Brief Healthcare in Rural NY – Current Challenges and Solutions for Improving Outcomes, in 2023, the NYS Comptroller produced a report titled, Rural New York: Challenges and Opportunities. That report focused on ten rural New York counties that share many characteristics with other of the state’s rural counties. There are four foundational challenges for rural communities in New York and nationally:

Low population density with widely distributed housing and services that hamper efforts to achieve economies of scale

Reliance on personal vehicles that results from a lack of public transportation – this reliance may disproportionately impact older adults and individuals with disabilities, but it also contributes to a general burden of vehicle maintenance, insurance, and fuel costs

Declining labor force and shrinking affordable housing as populations contract and age, and as rural areas increasingly become seasonal or recreational destinations for more affluent, transient populations, and

The persistence of challenges shared by the rest of the State, but that may be particularly challenging to address in rural communities, e.g., the opioid overdose epidemic and food insecurity.

Most of New York’s rural counties are designated as provider shortage areas by HRSA. Residents in three of the ten counties in the Report rely on neighboring counties to access hospital services, and in those counties that do have hospitals, services like obstetrics or behavioral health continue to diminish or be discontinued. It is important to appreciate the different nature of the challenges and potential solutions to accessing healthcare services for rural New Yorkers compared to urban and suburban New Yorkers.

A state-by-state report released in January 2026 by the University of Minnesota Rural Health Research Center, “displays county-level maps of changes in county-level hospital-based obstetric services availability between 2010 and 2023, highlighting changes that occurred between 2022 and 2023, along with time trends in the annual percentage of counties with in-county hospital-based obstetric services.” We see from the graph below that in New York, nearly ten percent of counties lost hospital-based obstetric services between 2010 and 2023, and most of those losses occurred in rural counties.

Locations of Maternity Services in New York

This section and the visualizations were developed by Adrienne Anderson, Senior Policy Fellow at the Step Two Policy Project.

As an alternative means of understanding the availability of maternity services in New York, we created a series of map-based, interactive data visualizations in Tableau. Several of these are presented in static form in the PDF version of this Brief, but are interactive on the Resources page of this website.

Data Sources:

Health Facilities Information System (HFIS)

Health Facility Certification Information dataset from health.data.ny.gov

Contains detail on services (i.e., “attributes”) offered at each facility

Matched on Facility ID #

Health Facility General Information dataset from health.data.ny.gov

Contains longitude and latitude for all facility site

Matched on Facility ID #

New York State Department of Health “NYS Health Profiles” lists of hospitals with perinatal services by level of care

Matched manually by Facility Name

List of Rural and Not Rural counties consistent with the 2023 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties

Matched on County Name

New York State GIS Data, for spatial data representing NYS Indigenous Territories

Methods:

The foundation of the visualizations is the New York State map with counties classified as either rural or not rural. On that foundation, we began to connect the data sources above within the Tableau environment to relate geographic information about facilities with data about their services. We also added a map layer of Indigenous Territories, where there are no hospitals, but where prenatal care may be available.

From the Health Facility Certification Information dataset, we downloaded one version with “Attribute Value” column filtered to include only “Maternity” or “Birthing Service O/P.” This became the basis for the inventory of labor and delivery sites statewide. From the NYS Health Profiles website, we imported a list of all perinatal care facilities by level of care.

Although the Health Facility Certification Information dataset was updated within a month of this Brief’s publication, stakeholders indicated that some of the entries did not reflect current reality. Further, some of the facilities listed in the NYS Health Profiles do not appear as operational Maternity facilities in the Health Facility Certification Information dataset.

Therefore, for the most accurate inventory, we removed facilities where maternity services have been confirmed to have closed, despite their continued presence in either data source. These included: St. Catherine of Siena in Suffolk County (listed as Level 2 in the NYS Health Profiles; does not appear in HFIS and sources report maternity closure as of 2024); Columbia Memorial Hospital (has 10 maternity beds listed in HFIS but has no corresponding level of perinatal care in the NYS Health Profiles and sources report its maternity services closed in 2020); and Ellis Hospital (listed as having “Maternity” services in HFIS, but has no beds listed and no perinatal level of care designation in the NYS Health Profiles – its Bellevue Women’s Care site is included).

In addition to known closures described above, there are occasionally temporary closures, such as at Brooks-TLC in Chautauqua County. Such closures can result from the loss of a specialist member of the care team, other staffing challenges, or temporary facility changes, such as during renovations (when they cannot be done in phases). Temporary bed and unit closures are not necessarily reflected in State data resources, so the overall instability of the availability of maternity services is likely understated in reporting.

Finally, following conversations with expert stakeholders, it became apparent that not all critical access hospitals (CAHs) would have the service capacity necessary to feasibly participate in the California pilot described later in this Brief. To further distinguish CAH services, we downloaded another version of the Health Facility Certification Information dataset with the “Description” column filtered to only include Critical Access Hospitals (CAH) and “Attribute Values” limited to either “Medical / Surgical” or “Medical/Surgical.” This represents the presence of surgical and anesthesia services, which would be essential components of providing standby perinatal services (e.g., in the case of emergency c-section or other obstetric emergency requiring surgical intervention).

Visualization 1: New York State Perinatal Facilities by Type and Level of Care

Levels of care: New York State recognizes a hierarchy of four levels of hospital-based perinatal care, as follows:

“Level 1 Perinatal Centers provide care to normal and low-risk pregnant women and newborns, and they do not operate neonatal intensive care units (NICUs);

Level 2 Perinatal Centers provide care to women and newborns at moderate risk and operate NICUs;

Level 3 Perinatal Centers provide care for patients requiring increasingly complex care and operate NICUs;

Regional Perinatal Centers provide the highest level of care and operate NICUs.” Regional Perinatal Centers are considered the lead perinatal facility for their regions.

In addition, New York State recognizes three classifications of Article 28 birthing centers (per 10 NYCRR Parts 754 and 795), which offer non-hospital-based birthing services to low-risk patients who require a post-birth length-of-stay of less than 24 hours.

Visualization 2: New York State Perinatal Facilities by Type and Level of Care with 15-mile Buffer, plus Critical Access Hospitals

This visualization is designed to model a 15-mile catchment surrounding each facility. The buffer does not account for access to roads, but major roads are included on the background map for reference. Terrain is also included in the background map but is more visible in the interactive versions.

We use a buffer of 15 miles modeled after a criterion of federal CAH designation: location is either more than 35 miles from the nearest hospital or CAH, or more than 15 miles away in areas with mountainous terrain or only secondary roads. We use this 15-mile buffer around maternity and birthing services to maintain consistency with the logic applied to CAH locations in the more rural areas of NY.

The colored squares from the previous visual are now circles of the same shades to represent the 15-mile circumference (i.e., buffer) around each site. The white squares below represent CAHs. All CAHs have a 24/7 emergency department, but as the next section will discuss, they do not necessarily have other services relevant to obstetric and neonatal care.

Three CAHs in New York State have maternity care on-site, so these appear as white squares at the center of a shaded 15-mile buffer circle.

California’s “Standby Perinatal Services” Pilot

Over the past decade, the closure of low-volume maternity units has left large swaths of rural California without timely access to hospital-based perinatal care, forcing pregnant patients to travel long distances for delivery or emergency obstetric services and worsening maternal and neonatal outcomes. In response, California enacted SB 669 in 2025 to test a new care model— “standby perinatal services”—designed to preserve emergency-ready obstetric and newborn care at rural critical access hospitals that can no longer sustain full, around-the-clock maternity units. The ten-year pilot authorizes selected hospitals to maintain a dedicated, prepared space with on-call physicians, midwives, and nurses able to respond within 30 minutes to urgent obstetric presentations or transfers, while meeting nationally recognized Level I maternal and neonatal care standards.

In California, SB 669: Rural hospitals: standby perinatal services was signed into law on October 11, 2025 (see Appendix C for bill text, status, votes, supporters and opponents, and analysis). It establishes a ten-year pilot program to permit critical access hospitals to deliver “standby perinatal services.” These services are defined as:

“… the provision of obstetric and neonatal medical care to patients who are transferred from an alternative birth center, or who present to the hospitals emergency department with an urgent or emergent obstetric issue, in a specifically designated area of the hospital that is equipped and maintained at all times to receive patients and capable of providing physician, midwifery, and nursing services within a reasonable time not to exceed 30 minutes.” [emphasis added]

The legislature’s rationale for this new category of perinatal service is as follows:

“(1) Over the past decade, rural hospitals with low volumes of deliveries have been closing their perinatal services largely because of workforce and funding challenges.

(2) These perinatal unit closures mean that large areas of rural California have no hospitals providing perinatal services, requiring long distances of travel to access an open perinatal unit.

(3) Studies in the United States and other developed countries show that newborn and maternal outcomes worsen when they reside more than 60 minutes from an open hospital perinatal unit, and that the outcomes are progressively worse with each additional hour of travel time.

(4) New models are needed to meet birthing persons needs in rural areas without hospital perinatal services.

(b) It is the intent of the Legislature to create a pilot project to test a new category of perinatal service, called standby perinatal services, in critical access hospitals in rural areas with limited access to comprehensive perinatal services.” [emphasis added]

By July 1, 2026, the California State Department of Public Health must establish the pilot project with up to five CAHs, the first two of which must be in certain specified counties. The CAHs applying to participate must be able to: meet the standards of standby perinatal services outlined in the bill; provide surgery and anesthesia as basic services of the hospital; obtain/perform timely blood gas, pH, and microbiologic analyses; maintain premixed infusions; maintain a basic emergency medical service, comprehensive emergency medical service, or standby emergency medical service licensed as a supplemental service; and have a designated room or rooms for the standby perinatal service space, with some caveats.[xxix]

The Department of Public Health will work with stakeholders to identify any additional requirements and to develop the data plan related to safety, outcomes, utilization, and populations served that must be collected and reported for the pilot project. The specific standby perinatal service and staffing requirements are identified in Section 3 of the bill text, which has been bolded in Appendix C. When delivering care, the providers of standby perinatal services must:

“Comply with the most recent standards and recommendations for Level I (Basic Care) of the Levels of Maternal Care and Level 1 (Well Newborn Nursery) of the Neonatal Levels of Care, within the Guidelines for Perinatal Care developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.”

The bill passed the California State Assembly (60 Democrats and 20 Republicans) and Senate (30 Democrats and 10 Republicans) unanimously, and there was no documented opposition. The stakeholders supporting the pilot can be seen on the Digital Democracy Calmatters webpage.

Standby Perinatal Services as an Option in New York

California’s forthcoming 10-year pilot may serve as a roadmap for addressing factors impacting the delivery of maternity services in rural New York. As we see from the discussion above, the requirements to provide standby perinatal services in California’s new pilot program are comprehensive and detailed. They differ most notably from New York’s current maternity services requirements in that they are “standby,” i.e., required to be available within 30 minutes, rather than at all times, and that the facility must be a CAH in a rural area with limited access to comprehensive perinatal services.

At their highest level, the requirement of having physician, midwifery, and nursing services available within 30 minutes; provide surgery and anesthesia as basic services; the ability to collect and perform basic lab analyses, to maintain and administer intravenous infusions and certain blood products; to provide emergency medical services; and to coordinate with EMS transportation are existing or achievable qualities in many of New York’s CAHs.

There are important challenges in rural counties that reflect statewide challenges related to the shortage of blood products, the strain on EMS agencies, and the shortage of EMS personnel. Interfacility transport of patients in a perinatal crisis, potentially lasting multiple hours, would require a level of competence requiring the administration of IV medications, blood products, and hemodynamic monitoring.

Considering the possibility of adopting California’s roadmap for standby perinatal services would require New York to also address these other challenges in the matrix of rural healthcare delivery.

Current Perinatal Service Requirements in New York

Hospitals

The specifics in the California statute may not be fully transferable to develop a similar pilot in New York, but they can certainly work as a road map to explore the idea. As we see from New York’s hospital perinatal services regulations, the foundations are not dissimilar to those in California.

In New York, Section 405.21 of Title 10 of New York Codes, Rules and Regulations provides requirements for hospitals that provide maternity and newborn services – from preconception and prenatal care through labor, delivery, postpartum, and neonatal services. Hospitals must operate in alignment with professional standards, maintain qualified obstetric, pediatric, nursing, and other staff, participate in New York’s perinatal regionalization system, and adhere to the regulations in Part 721 of Title 10 relevant to their level of care designation.

Requirements include written policies for clinical care, infection control, rooming-in, emergency preparedness, neonatal stabilization, quality improvement, maintenance of closed, secure perinatal units, and coordination with affiliated hospitals and free-standing birth centers. Hospitals are required to have services to: identify high-risk pregnancies, provide continuous electronic fetal monitoring, perform a Cesarean delivery within 30 minutes of determining the need, administer anesthesia services 24-hours a day, and provide radiology and ultrasound services, with at least one ultrasound machine immediately available for use by the labor and delivery unit. Hospital-based perinatal services must also include 24-hour blood type and cross-matching services, basic emergency laboratory evaluations, and availability of certain blood products at all times.

Potential Locations in New York

If we consider locations in rural New York where potential standby perinatal services pilots could be deployed, there are several factors to consider:

Presence of a critical access hospital

The scoring factors for Maternity Care Target Areas

Population-to-full-time-equivalent maternity care health professional ratio

Percent of population at or below 200 percent of FPL

Travel distance to nearest source of accessible care outside of the MCTA

Fertility rate

Social vulnerability

Pre-pregnancy obesity

Pre-pregnancy diabetes

Pre-pregnancy hypertension

Cigarette smoking

Prenatal care in the 1st trimester

Behavioral health factor

Rates of existing severe maternal morbidity

Population of women of reproductive age

All of these data sets are available through the MCH Dashboard, the Prevention Agenda Dashboard, other DOH sources such as the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), HRSA Data Warehouse (Maternal and Infant Health Mapping Tool), and the American Community Survey (ACS).

The visualization below depicts the locations of maternity services and the pilot-eligible critical access hospitals.

Visualization 3: Location of New York State Critical Access Hospitals Relative to Maternity and Birthing Services, plus 15-mile Buffer

Here, colored squares indicate the presence of maternity and birthing services by level of care, as in Visualization 1; CAHs are depicted as circular buffers (representing 15 miles), shaded in translucent white or black according to their services available (i.e., medical/surgical, or no medical/surgical, respectively. In separately reviewing public information about each CAH, one of the CAHs with medical/surgical services appears to only have ambulatory surgery services, and another appears to only have post-operative surgical recovery services. All colors are labelled in the key on the left-hand side.

Conclusion

Rates of maternal death continue to rise, as do rates of severe maternal morbidity, which is much more common. Over the past 15 years in New York, rates of severe maternal morbidity (considered to be a “near miss” of a maternal death), has increased almost 70 percent.[xxx] With the persistent rise in New York’s maternal morbidity and mortality rates due in part to factors such as racism, bias, structural inequities, lack of access to services, poor preconception health/high rates of maternal chronic illness, and increasing rates of behavioral health conditions, it is reasonable to look at innovative policy solutions from other states.

Many counties in New York that are not designated as “rural” by the NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties also have limited access to healthcare services in general, and maternity services in particular. Rural and “rural look-alike” counties lack sufficient healthcare-supportive infrastructure, such as robust EMS, adequate internet access and bandwidth, and transportation options beyond personal vehicles, to name just a few challenges.

One of the most pressing needs in the effort to address climbing rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in rural New York is access to services. Within the context of closing hospitals and OB units, the distance between locations of maternity services is growing, and with increasing distance, risk also rises. California’s standby perinatal services pilot is designed to mitigate the well-researched risk that accompanies prolonged travel time to perinatal services.[xxxi] The pilot is not a replacement for full-time, comprehensive, person-centered care, but it may present an important opportunity to mitigate some of the worst potential outcomes.

The updated CMS Conditions of Participation for emergency services readiness in critical access hospitals is an important effort to better manage maternity emergencies in the absence of hospital-based OB services. New York’s Regional Perinatal Centers are important partners in developing this expertise. To augment this enhanced expertise, facilitating non-OB CAHs that have current surgical services and that are more than 15 miles away from existing maternity services to provide standby perinatal services could also address some of the distance-to-care risk, and complement many of the State’s other rural-tailored efforts. Areas such as Wyoming, Orleans, southern Madison/northern Chenango, Franklin, Schoharie, and/or Delaware counties, as shown above in Visualization 3 (as the white circles), where there are no existing maternity services, could be ideal locations for a New York-tailored standby perinatal services pilot. In addition to the RPCs, the rural ambulance agencies would also be important partners to ensure appropriate resources and expertise are in place for the transport of patients to the definitive level of care.

The CMS Report from May 2022 focused on Advancing Rural Maternity Health Equity includes many potential solutions to address challenges in care disparities; financial challenges; inadequacies in training, equipment and workforce; and building regional relationships. Some of the recommendations are in place in New York, and others are yet to be. As we seek to build a more equitable and accessible healthcare delivery system for all New Yorkers, establishing a standby perinatal services pilot in areas where there is no care could be an important step in improving the outcomes of mothers and babies in rural New York.

Appendix A – Maternity Care Target Areas (MCTAs) Scoring

Appendix B – Key Definitions

Pregnancy-associated death: a death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy

Pregnancy-related death: a death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy

Pregnancy-associated, not related death: a death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from a cause that is not related to pregnancy

Pregnancy-associated, unable to determine relatedness death: a death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy where it cannot be determined from the available information whether the cause of death was related to pregnancy

Maternal mortality: the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of the end of pregnancy, excluding deaths from accidental or incidental causes

Maternal mortality ratio: number of maternal mortalities per 100,000 live births in a given year

Pregnancy-related mortality ratio: number of pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 live births in a given year

Severe Maternal Morbidity: refers to a group of potentially life‑threatening health conditions or complications that occur unexpectedly during childbirth. Severe maternal morbidity can result in short- and long‑term consequences for the health and wellbeing of birthing people beyond pregnancy.

Appendix C – California Bill Text

Version: Chaptered (10/11/2025)

The people of the State of California do enact as follows:

SECTION 1.

(a) The Legislature finds and declares all of the following:

(1) Over the past decade, rural hospitals with low volumes of deliveries have been closing their perinatal services largely because of workforce and funding challenges.

(2) These perinatal unit closures mean that large areas of rural California have no hospitals providing perinatal services, requiring long distances of travel to access an open perinatal unit.

(3) Studies in the United States and other developed countries show that newborn and maternal outcomes worsen when they reside more than 60 minutes from an open hospital perinatal unit, and that the outcomes are progressively worse with each additional hour of travel time.

(4) New models are needed to meet birthing persons needs in rural areas without hospital perinatal services.

(b) It is the intent of the Legislature to create a pilot project to test a new category of perinatal service, called standby perinatal services, in critical access hospitals in rural areas with limited access to comprehensive perinatal services.

SEC. 2. Section 1256.05 is added to the Health and Safety Code, immediately following Section 1256.01, to read:1256.05.

(a) For purposes of this section and Section 1256.06, the following definitions apply:

(1) Critical access hospital means a hospital designated by the State Department of Public Health as a critical access hospital, and certified as such by the Secretary of the United States Department of Health and Human Services under the federal Medicare Rural Hospital Flexibility Program.

(2) Department means the State Department of Public Health, unless otherwise specified.

(3) Standardized order sets means predefined groups of orders that support clinical decisions, including, but not limited to, appropriate treatments, medications, and dosages, for specific conditions or procedures and that are developed using relevant evidence-based guidelines.

(4) Standby perinatal services means the provision of obstetric and neonatal medical care to patients who are transferred from an alternative birth center, or who present to the hospitals emergency department with an urgent or emergent obstetric issue, in a specifically designated area of the hospital that is equipped and maintained at all times to receive patients and capable of providing physician, midwifery, and nursing services within a reasonable time not to exceed 30 minutes.

(b) The department shall do all of the following:

(1) By July 1, 2026, establish a 10-year pilot project within up to five critical access hospitals to allow participating hospitals to establish standby perinatal services. If qualified, the first two hospitals selected shall be nonprofit and located in the County of Humboldt and the County of Plumas. Up to three additional critical access hospitals may be selected at any time if the application includes a signed agreement from the exclusive employee representatives of the workforce that the proposed pilot project site would not adversely impact the workforce or includes an attestation that there is no existing exclusive employee representative.

(2) Within a reasonable time, determine whether hospitals requesting to participate meet applicable statutory requirements, including, but not limited to, all of the following:

(A) Ability to meet the standards of the standby perinatal service, as described in Section 1256.06.

(B) Provide surgery and anesthesia as basic services of the hospital.

(C) Maintain capability for obtaining or performing timely blood gas, pH, and microbiologic analyses.

(D) Provide ability to maintain premixed infusions.

(E) Maintain a basic emergency medical service, comprehensive emergency medical service, or standby emergency medical service licensed as a supplemental service.

(F)(i) Have a designated room or rooms for the standby perinatal service space. A hospital may designate an existing room or rooms with a licensed general acute care bed as the standby perinatal service space. If a hospital designates an existing room or rooms for the standby perinatal service space, the hospital may continue to provide general acute care services in that room or rooms when the room or rooms are not in use by the standby perinatal services only if all remaining general acute care beds are occupied or a plan for management of perinatal patients using alternate space is approved by the department.

(ii) The operating room may serve as the delivery room in hospitals having a licensed bed capacity of 25 or less, but the operating room shall not serve as the sole standby perinatal service space.

(G) In consultation with stakeholders, establish any additional requirements that the department deems necessary to protect patient safety or to ensure quality of care under the pilot project.

(3)(A) Develop a template to collect and evaluate data on safety, outcomes, utilization, and populations served under the pilot project using stratified demographic data, to the extent statistically reliable data are available and comply with medical privacy laws and practices. The department may, in consultation with relevant stakeholders, establish additional requirements for participating hospitals to collect and report any additional data under the pilot project that the department deems necessary.

(B) Compile the data collected pursuant to subparagraph (A), prepare and submit an evaluation to the Legislature, and make the evaluation publicly available. The department shall submit the evaluation to the Legislature on or before two years after the completion of the pilot project. Data-collection requests shall be provided in a timely manner to enable the pilot hospital to collect and report the data before the deadline. The evaluation to be submitted to the Legislature pursuant to this subparagraph shall be submitted in compliance with Section 9795 of the Government Code.

(4) Consult with relevant state departments and stakeholders on the matter of meeting the requirements of this subdivision. Stakeholders shall include representatives of hospitals, consumers, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Nurse-Midwives, health plans, labor, and other health care professionals who provide pediatric and pregnancy-related services, including, but not limited to, registered nurses, certified nurse-midwives, and licensed midwives.

(c) A hospital seeking to participate in the pilot project shall submit an application to the department.

(d) An approved standby perinatal service shall be subject to all relevant licensing enforcement provisions as established under this chapter and Chapter 1 (commencing with Section 70001) of Division 5 of Title 22 of the California Code of Regulations.

(e) If, at any time, a hospital with a standby perinatal service fails to meet the requirements set forth in this section or Section 1256.06, or fails to ensure patient health and safety, as determined by the department, the department may suspend or revoke its approval of the hospitals participation in the pilot project.

(f)(1) Notwithstanding any other law or regulation, a hospital participating in the pilot project may, in consultation with the medical and any other relevant staff, request program flexibility for the statutory requirements of this section or Section 1256.06, in order to meet the particular capacities and needs of the hospital and community.

(2) If the department approves the request described in paragraph (1), the departments approval shall provide for the terms and conditions under which the program flexibility is granted.

(3) To request program flexibility for the statutory requirements of this section or Section 1256.06, the hospital shall follow existing procedures established by the department for program flexibility requests pursuant to subdivision (b) of Section 1276.

(g) Notwithstanding any other law, the department may, without taking any regulatory actions pursuant to Chapter 3.5 (commencing with Section 11340) of Part 1 of Division 3 of Title 2 of the Government Code, implement, interpret, or make specific this section and Section 1256.06 by means of an All Facilities Letter (AFL) or similar instruction.

SEC. 3. Section 1256.06 is added to the Health and Safety Code, immediately following Section 1256.05, to read:1256.06. [emphasis added]

A hospital requesting approval to establish a standby perinatal service pursuant to Section 1256.05 shall implement and maintain all of the following requirements:

(a)(1) Comply with the most recent standards and recommendations for Level I (Basic Care) of the Levels of Maternal Care and Level 1 (Well Newborn Nursery) of the Neonatal Levels of Care, within the Guidelines for Perinatal Care developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

(2) Have the capacity for operative delivery, including caesarean section, and neonatal resuscitation and stabilization at all times.

(3) Have the ability, equipment, and supplies necessary to provide care for mothers and infants needing emergency or immediate life support measures to sustain life up to 12 hours or to prevent major disability, including, but not limited to, all of the following services:

(A) Administration of intravenous or intramuscular antibiotics.

(B) Administration of intravenous or intramuscular uterotonic drugs, including oxytocin.

(C) Administration of intravenous or intramuscular anticonvulsants.

(D) Administration of antihypertensives.

(E) Manual removal of the placenta.

(F) Removal of retained products of conception.

(G) Basic neonatal resuscitation.

(H) Surgery, including caesarean sections.

(I) Blood transfusions.

(J) Additional services specified by the department, in consultation with relevant stakeholders.

(4) Have capabilities for risk identification and determination of conditions necessitating consultation, referral, and transfer.

(5) Have capabilities, including necessary equipment, for stabilization and the ability to facilitate transfer or transport to a higher level of care at all times.

(6)(A) Have the equipment and supplies specified in Section 70551 of Title 22 of the California Code of Regulations, or its successor.

(B) In addition to the items required under subparagraph (A), have all of the following equipment and supplies:

(i) A fetal heart rate monitor that includes both the ability to monitor multiple gestation pregnancies using internal monitors, including fetal scalp electrodes and intrauterine pressure catheters, and maternal pulse integrated to ensure monitoring of fetal pulse and not maternal pulse.

(ii) Provision for oxygen and suction for the mother and infant, including, but not limited to, specialized supplies needed for neonatal resuscitation and breathing support.

(iii) A ventilatory assistance bag and infant masks of assorted sizes for infants of different gestational ages.

(iv) A postpartum hemorrhage kit, including a uterine tamponade device.

(v) Neonatal resuscitation supplies, including supplies for umbilical access for medications.

(vi) Maternal steroid medications available for initial administration in the case of preterm labor while awaiting transport.

(vii) A refrigerated medication storage unit in the standby perinatal service for uterotonic medications requiring refrigerated storage to be immediately accessible in emergencies.

(viii) A suction device appropriate for neonatal resuscitation.

(b)(1) In consultation with the medical staff, define the responsibilities of the medical staff and administration associated with the standby perinatal services.

(2)(A) Ensure that a provider that provides services pursuant to this section in the hospital meets all applicable requirements set forth in both of the following:

(i) The medical staff bylaws.

(ii) Rules, regulations, and policies of that facility.

(B) Nothing in this section shall be construed to require changes to the medical staff bylaws or policies regarding credentialing or privileges.

(c)(1) Ensure that a physician who is certified, or eligible for certification, by the American Board of Obstetrics and Gynecology, the American Board of Pediatrics, or the American Board of Family Medicine, and who is a member of the medical staff of the facility, has overall responsibility of the standby perinatal services.

(2) The physician described in paragraph (1) shall be responsible for ensuring that contracts and agreements are in place as applicable and for the development of policies and procedures for all of the following:

(A) Developing policies and procedures specified in paragraphs (1) through (28) of subdivision (b) of Section 70547 of Title 22 of the California Code of Regulations that align with the standards specified in paragraph (1) of subdivision (a).

(B) Admission policies for infants transferred from an alternative birth center.

(C) Consultations, including, but not limited to, real-time telemedicine services, between the standby perinatal service and health care personnel from an intensive care newborn nursery and from a perinatal service, qualified and available at all times to provide maternal fetal medicine consultation.

(D) Formal arrangements for consultation or transfer of an infant to an intensive newborn nursery and a mother to a hospital with the necessary services for medical problems beyond the capability of the standby perinatal services.

(E) Current state newborn screening requirements.

(F) Standby perinatal service activation protocols.

(G) Condition-specific management protocols outlining best practices.

(H) Emergency codes.

(I) Monitoring and checkoff to ensure that equipment stays in the standby perinatal service and does not outdate.

(J) Documentation standards for antepartum, intrapartum, postpartum, and newborn care.

(K) Surgery and anesthesia services readily available at all times.

(L) Arrangements for incidents of more than one patient requiring the use of the designated standby perinatal service space.

(M) Care management for mothers, fetuses, and neonates in alignment with the standards specified in this section.

(N) Development by an appropriate committee of the medical staff of standardized obstetric and newborn nursing procedures and standardized order sets for pregnant patients presenting to the emergency department and for the standby perinatal service, and for neonates. Standardized order sets shall be annually reviewed and updated as necessary.

(O) Convening of an appropriate obstetric and neonatal or pediatric committee that, at a minimum annually, evaluates the services provided and makes appropriate recommendations to the executive committee of the medical staff and administration.

(d) In consultation with the physician described in subdivision (c) and with other appropriate health care professionals, do all of the following:

(1) Implement and maintain contracts, and transfer agreements as applicable, and develop and implement policies and procedures for any maternal or neonatal care outside the scope of the standby perinatal service, including, but not limited to, all of the following services:

(A) Transfer of mothers and neonates to appropriate higher levels of care, including a reliable, accurate, and comprehensive communication system between hospitals initiating and hospitals receiving a patient transfer from a standby perinatal service, hospital personnel, and transport teams.

(B) A blood bank, if the facility might need additional blood.

(C) Ambulance transport and rescue services.

(2) Develop a system for ensuring coverage to provide care for both the mother and the neonate, on call 24 hours a day for the standby perinatal service, including, but not limited to, both of the following:

(A) Physician and nursing staff coverage onsite within 30 minutes.

(B) A roster of physicians and certified nurse-midwives who have an agreement or contract with the hospital, and their immediate contact information, who are available to provide emergency perinatal services.

(3) Have a registered nurse immediately available within the hospital to provide nursing care, including emergency maternal fetal triage and infant resuscitation.

(4) Develop a roster of specialty physicians who have an agreement or contract with the hospital, and their immediate contact information, who are available for consultation at all times.

(5) Conduct monitoring and checkoff to ensure that equipment stays in the standby perinatal service and does not outdate.

(6) Ensure continuing education for the medical staff.

(7) Establish, and document compliance with, continuing education and training program requirements for nursing staff in perinatal nursing and infection control, including, but not limited to, all of the following:

(A) Biennial, week-long rotations at a Level II, III, or IV maternal or neonatal care facility.

(B) Participation in simulation-based training to reinforce response to obstetric emergencies.

(C) All other continuing education and training programs that are necessary to ensure the safe provision of care for both mothers and neonates in the standby perinatal service.

(8)(A) Annually verify and document all nursing competencies, including, but not limited to, maternal care, fetal and newborn care, postdelivery care, and emergency condition competencies.

(B) Maintain evidence of continuing education and training programs for the nursing staff in perinatal nursing and infection control, including all of the following:

(i) Documented current registered nurse license.

(ii) Current Basic Life Support (BLS) certification.

(iii) Current Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS) certification.

(iv) Electronic fetal monitoring certification.

(v) S.T.A.B.L.E. neonatal education program certification.

(vi) Neonatal resuscitation program certification.

(e) Require a physician, certified-nurse midwife, or registered nurse to attend to patients, within the scope of their licensure, under the effect of anesthesia or regional anesthesia, when in active labor, during delivery, or in the immediate postpartum period.

(f) Initiate and sustain an education program and develop a quality improvement program to maximize patient safety, in collaboration with facility partners that provide higher levels of care.

(g) Comply with the existing licensed nurse-to-patient ratios for a combined labor/delivery/postpartum area of perinatal services. This subdivision does not alter or amend the effect of any regulation adopted pursuant to Section 1276.4.

(h) Report the data required by Section 1256.05 quarterly and in the manner and method required by the department.

(i) Maintain compliance with federal Medicare obstetrical services conditions of participation, if applicable.

SEC. 4.

The Legislature finds and declares that a special statute is necessary and that a general statute cannot be made applicable within the meaning of Section 16 of Article IV of the California Constitution because of the unique circumstances of the County of Humboldt and the County of Plumas with regard to access to perinatal services. Residents of those counties do not have adequate access to perinatal services, but they could have access to hospitals with capacity to provide services using a standby perinatal model. A special statute applied to those counties would expedite implementation of that model.

SEC. 5.

No reimbursement is required by this act pursuant to Section 6 of Article XIIIB of the California Constitution because the only costs that may be incurred by a local agency or school district will be incurred because this act creates a new crime or infraction, eliminates a crime or infraction, or changes the penalty for a crime or infraction, within the meaning of Section 17556 of the Government Code, or changes the definition of a crime within the meaning of Section 6 of Article XIIIB of the California Constitution.

Endnotes

[i] Perinatal – prenatal (before birth), intrapartum (onset of labor – delivery of the placenta), and postpartum (immediately following delivery – 6/8 weeks)

2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

NYS Live Births | 225,162 | 220,536 | 207,590 | 209,947 | 206,812 |

[iii] “The level of maternity care access within each county is classified across New York by the availability of birthing facilities, maternity care providers, and the percent of uninsured women.” Fontenot, J., et al. Where You Live Matters: Maternity Care Deserts and the Crisis of Access and Equity in New York. March of Dimes. 2023.

[iv] NYS: NEW YORK STATE REPORT on PREGNANCY ASSOCIATED DEATHS in 2021, 2025; NYC: Pregnancy Associated Mortality in New York City, 2022, 2025.

[v] System: Interacting entities that support services before, during, or after a pregnancy, such as health care systems, payors, and public services and programs. Facility: A physical location where direct care is provided, such as small clinics and urgent care centers as well as hospitals with trauma centers. Provider: An individual with training and expertise who provides care, treatment, or advice. Community: A grouping based on a shared sense of place or identity, such as physical neighborhood, as well as communities based on common interests or other shared circumstance. Patient or family: An individual before, during, or after a pregnancy and their family, internal or external to the household, with influence on the individual.

[vi] Severe maternal morbidity is defined by the CDC as, “includes unexpected outcomes of labor and delivery that can result in significant short- or long-term health consequences.”

[vii] Obstetric Volume and Severe Maternal Morbidity Among Low-Risk and Higher-Risk Patients Giving Birth at Rural and Urban US Hospitals, JAMA Health Forum, June 24, 2023.

[viii] A pregnancy-related death is defined as “a death during pregnancy or within one year of the end of pregnancy from a pregnancy complication, a chain of events initiated by pregnancy, or the aggravation of an unrelated condition by the physiologic effects of pregnancy.” The pregnancy-related mortality ratio (deaths per 100,000 live births) is calculated as: (number of pregnancy-related deaths/number of live births) x 100,000.

[ix] State Health Department Leads Several Initiatives to Reduce Pregnancy-Related Deaths and Improve Health Outcomes, March 14, 2024.

[x] We use the terms “maternal,” “women,” or “mothers” in this Policy Brief, but we appreciate that people of various gender identities give birth and receive services.

[xii] Haiman MD, Cubbin C. Impact of Geography and Rurality on Preconception Health Status in the United States. Prev Chronic Dis 2023;20:230104. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd20.230104

[xiv] Maternal mortality rate per 100,000 live births – “The number of deaths to women from any causes related to or aggravated by pregnancy or its management that occurred while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy (ICD-10 codes O00-95, O98-O99, and A34 (obstetrical tetanus)) per 100,000 live births. Note: The maternal mortality definition has been revised to be consistent with the definition used by the World Health Organization. The previous definition used by NYSDOH (ICD 10 codes: O00-O99) to report maternal mortality included deaths that occurred outside this time period (ICD 10 codes: O96 and O97).”

[xvi] CDC, Identifying Severe Maternal Morbidity (SMM), May 15, 2024.

[xvii] Call to Action to Quantify Non-Severe and Severe Maternal Morbidity, Dreisbach, C., Yu, Y., Groth, S., Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, Volume 54, Issue 2, 131 – 136.

[xix] Metro/Nonmetro: The Metro group includes counties in these Urbanization categories: Large Central Metro, Large Fringe Metro, Medium Metro, and Small Metro. The Nonmetro group includes counties in these Urbanization categories: Micropolitan (non-metro) and Noncore (non-metro).

[xx] KFF, Medicaid and CHIP Eligibility, Enrollment, and Renewal Policies as States Resume Routine Operations, April 1, 2025.

[xxi] NYS DOH, Expanded Income levels for Children and Pregnant Adults, February 2025.

[xxiii] NYS DOH, Maternal Mortality Review Board, New York State Report on Pregnancy-Associated Deaths in 2021, 2025.